Guide to cat behaviour

Guide to cat behaviour

Our cats are fascinating and complex creatures. Read on to discover a little bit more about what makes them tick – what sort of emotions they may experience, how they communicate, and how, as a human in their lives, you can help them to feel safe, happy, and comfortable.

Introduction

Cats are individuals. Each cat varies in how sociable they’ll want to be with humans and other animals. They also have individual preferences (for example, in how they like to interact and play, where they like to rest, and how they like to spend their time) and individual responses to situations (which are influenced by factors such as their previous experiences and personality).

Cats have a flexible social system. This means they can choose to live alone or in groups of compatible cats (if there are adequate resources). Because of their flexible social system, they often display behaviours that are intended to keep distance between individuals, such as growling or making their hair stand on end to make themselves look bigger and more intimidating. But they do also display behaviours that facilitate social interaction, like rubbing against each other.

Cats prefer to be self-sufficient. Even when living with humans or other animals, cats want to rely on themselves for protection and survival rather than others. So, to feel safe, cats need a familiar, positive, and predictable environment that they feel they have control over, as well as feeling they have control over their interactions with other individuals (other cats, humans, and other animals).

Cats display a range of emotions. Like us, cats are complex animals who have long term memory and learn from both positive and negative experiences. Rather than simply thinking of cat emotions as good or bad, we can think of them in categories which include engaging emotions (where the cat actively seeks out something that benefits them) and protective emotions (where the cat protects themselves from harm).

Cats communicate with a range of senses. This includes touch (like rubbing up against other individuals and grooming each other), smell (leaving scent signals, scratching, and urine spraying), sight (using facial expressions or certain body postures to communicate with others), and hearing (purrs, trills, chirps, meows, growls, hisses – and more!).

Understanding body language

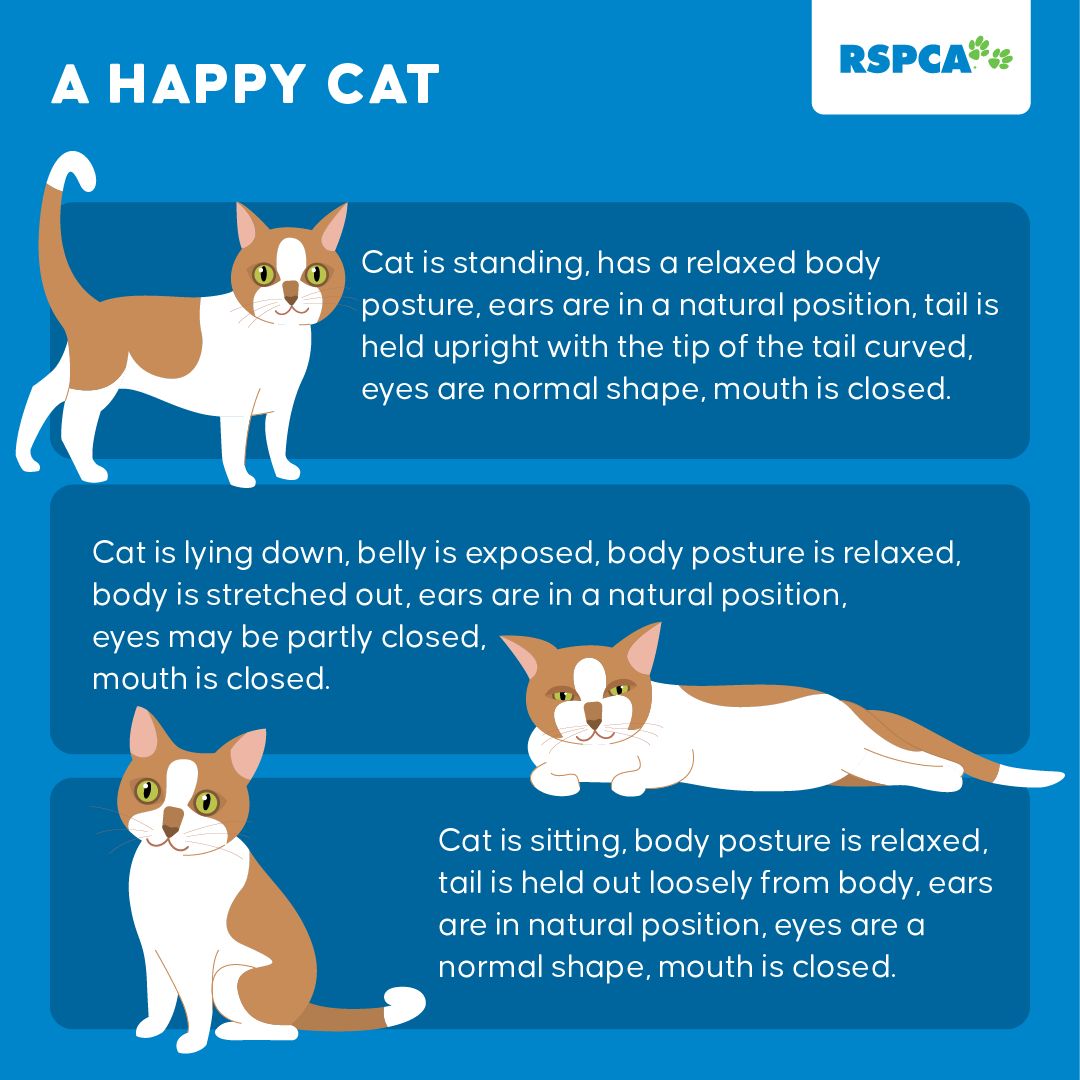

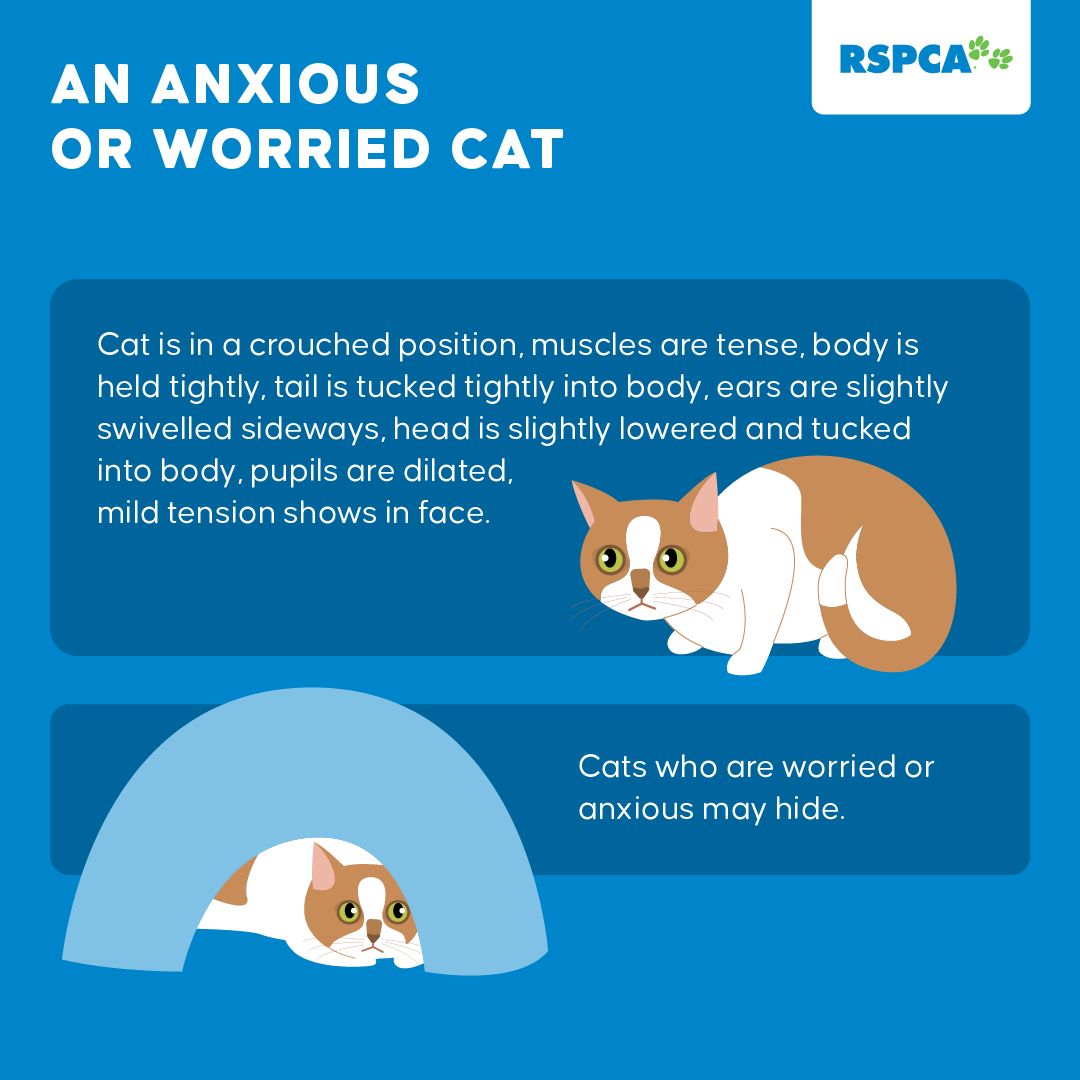

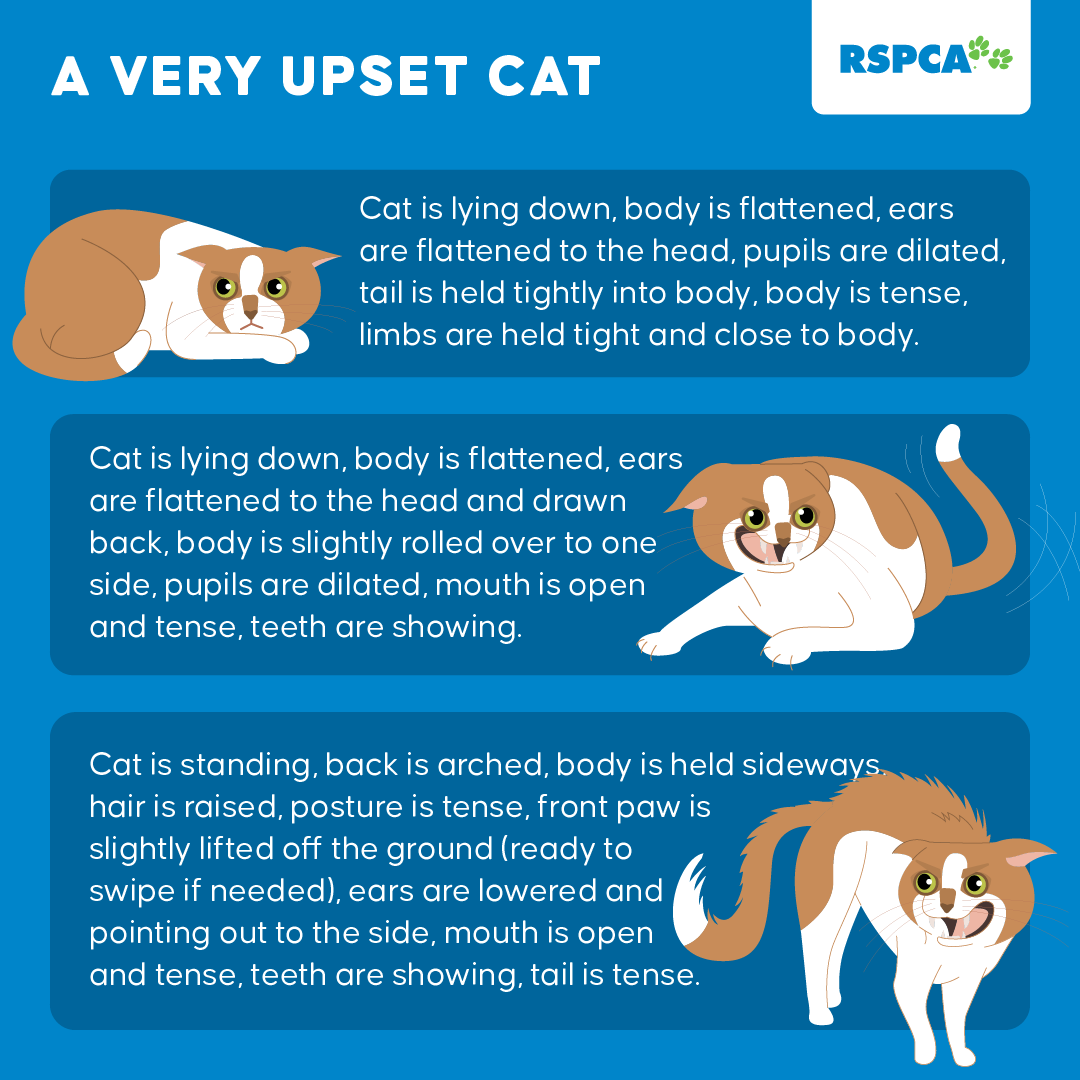

It’s important to learn about your cat’s body language and, when interacting with them, watch to see how they are feeling about the interaction. If they seem uncomfortable, it’s best to stop and let them move away if they want to.

A cat’s body language can be subtle, so it’s not always easy to accurately read how they’re feeling. To help you understand what your cat is feeling and trying to communicate, look at his or her eyes, tail, mouth, and posture and use this guide to help you recognise important body language signals.

How do cats communicate?

Cats communicate with you and each other in many different ways, with a range of signals using their different senses. Understanding these can help you to communicate with your cat, improve the quality of your interactions, and help them have positive experiences and good welfare.

What emotions can cats experience?

Cats are complex sentient animals who have long-term memory and learn from both positive and negative experiences which influence their mental state, welfare, and future behaviour . Their cognitive and emotional health (for which together we use the term mental wellbeing) are just as important as their physical health. For a cat to experience optimal wellbeing and welfare, both their physical and mental needs must be met.

Cats can respond to situations with a range of emotions (feelings) that result from the influence of a combination of their current circumstances (including their nutrition, physical environment, and health) and their behavioural interactions with other cats, other species (including humans), and the cat’s previous experiences. The cat’s emotional state influences their behavioural response to situations.

Feline emotions/feelings

Emotions, feelings, perceptions, and experiences matter to individual cats and these have an impact on their welfare. So, it is important that we consider and understand these to help our cats live their best lives,

Although we can’t measure the emotions and feelings of cats directly as they are subjective (unique to that cat – only the cat knows how they feel just as only you know how you feel), there are models developed by the veterinary and animal science community to help us to understand what our cats might be experiencing.

One way of describing and thinking about feline emotions and behaviour that is widely used is the Heath Model of emotional health (Heath 2018, Heath et al 2022). This model uses the terms engaging and protective emotions and behavioural responses and is used here to illustrate why the cat might experience certain emotions and how these emotional motivations may trigger specific behaviours.

Although it’s common for emotions to be classified as either positive or negative, this terminology implies that the emotions and resulting behaviours are good or bad. This is an oversimplification and does not reflect that all emotions and behavioural responses - when triggered appropriately – can benefit and protect the cat and safeguard their welfare and survival.

Engaging emotions which lead to engaging behavioural responses

Engaging emotions lead to behaviours in which the cat actively seeks out and engages with something (e.g., food, water, shelter) that results in benefit to their survival and satisfaction:

- Desire-seeking emotions that motivate the cat to seek out opportunities for attention, comfort, food, water, and shelter. For example, the voice of a familiar person with whom the cat has had consistent and positive experiences in the past can trigger positive and engaging emotions in the cat, who may then respond with engaging behavioural responses such as approaching the person and rubbing against them soliciting attention.

- Social play emotions that motivate the cat to interact with others to obtain information about their own social competence and potential. This emotion is often strongest in kittens, who are learning how to interact with other cats and species.

- Lust emotions that motivate the cat to find and mate with another cat. In desexed cats, these emotions are not likely to be very relevant to their behaviour but are highly relevant for non-desexed cats.

- Care emotions that motivate the cat to maintain bonds with offspring and display nurturing behaviour towards others. This may include spending time with others and grooming.

Protective emotions which lead to protective behavioural responses

These are emotions that aim to protect the cat from harm and ensure the cat’s survival:

- Fear–anxiety emotions that motivate the cat to try and protect their access to essential resources such as shelter, food, and water, and manage threats to their personal or resource security to safeguard their survival. In general, fear is the emotion triggered when the cat perceives the threat as real, immediate, and present, while anxiety is a response to a perceived threat which the cat is uncertain about (e.g., anxiety about something that the cat feels might happen). Fear and anxiety emotions often result in behaviours which try to increase distance from or avoid an interaction with a perceived threat.

- Pain emotions that are felt when the body is physically damaged in some way. Pain is experienced as both a physical sensation and as an emotional state. The pain emotional state is associated with acute and chronic pain and can have a learned component. Pain emotions motivate the cats to protect themselves from physical harm and discomfort.

Previous experiences may make the fear, anxiety, and pain emotions more likely to be triggered; for example, if a cat has had a painful experience at the veterinary clinic, they might be more likely to experience anxiety and fear the next time they go, even if that visit itself is not associated with any physical pain.

- Frustration emotions result from a situation in which the cat has lost their control in a situation, been unable obtain resources when they want them, or has received nothing or a less desirable outcome than they expected (e.g., they couldn’t access food when they wanted to or received less food [or less desirable food] than they wanted). Frustration motivates the cat to try and access the resource that they want but have been denied, and to protect and defend what they do have due to the perceived threat of losing what they have. An inadequate environment that does not meet the cat’s needs is likely to trigger frustration emotions.

Frustration is often triggered along with one of the other protective emotions and intensifies and accelerates the behavioural responses to these emotions. This is commonly seen in cats who have a lack of or perceived lack of control and so an inability to react to a threatening situation and protect themselves. In this situation they may be more likely to display intense versions of behavioural responses to other emotions such as fear, such as a cat who is restrained and fearful being more likely to bite than they would normally because they cannot run away and hide.

- Panic–grief emotions are generally displayed by kittens when they are young and unable to protect themselves. For example, kittens crying when they are separated from their mother, to try and get their mother's attention. It is thought that these emotions may also be displayed by an adult cat in response to the loss of an individual to whom they are closely bonded.

Protective emotions are associated with behaviours which attempt to:

- Increase distance from and/or decrease interaction with the situation which has triggered the emotion. These protective behavioural responses include avoidance (e.g., eye avoidance [looking away] and running away) and repulsion (e.g., doing something which is designed to get the threat to move away, these include active behaviours like hissing, swiping, and biting and also passive behaviours such as staring or blocking access).

- Gather more information about the situation which has triggered the emotion. These protective behavioural responses are either passive or active. The passive protective behavioural response is called inhibition and is the cat using their sensory systems to gather information passively, including listening, looking, watching, sniffing, usually while the cat remains at some distance from the trigger. In intense emotional situations, inhibition may manifest as a ‘freeze’ response. The active protective behavioural response is called appeasement and involves the cat interacting with the emotional trigger in order to gather information and, at the same time, offering signs of non-hostility in return; for example, the cat actively giving and gathering information from another familiar individual by vocalising (in a non-hostile way) and then listening for a response so they can decide what to do. Appeasement is less common in cats than inhibition due to their natural state as a solitary hunter and survivor.

Cats may experience multiple emotions at the same time or switch quickly between them. Sometimes, the cat may experience emotional conflict if they feel two opposing emotions at the same time (such as desire for food but fear of the environment where the food can be accessed, so the cat both wants to move towards the food but also wants to avoid the feared environment).

Allowing the cat to successfully use their range of behavioural responses reduces the likelihood that the emotion and behavioural response will increase in intensity. For example, if a fearful cat is allowed to use an avoidance response and hide, this makes it less likely that their fear will intensify, and they will feel the need to run away or change their response to a repulsion response (e.g., growling or striking/scratching to try and make whatever or whoever is causing them fear to move away). Understanding the cat’s need to express the protective behavioural response of hiding and allowing them to successfully hide will allow them to feel safer and more in control, it helps them to recover from the emotion of fear back to a more neutral emotional state. In addition, it can also reduce the likelihood that they will get frustrated. This is important, as frustration will only intensify and accelerate the other emotions and responses.

Now that you know a little bit more about how your cat might think and feel, you can use this knowledge to help them feel safe, happy and comfortable at home. Read the rest of our Safe and Happy Cats guide to find out more.

This guide is based on and adapted from information in the following literature, where you can find more information: Ellis SL et al (2013) AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines, Taylor S et al (2022) IFSM/AAFP Cat Friendly Veterinary Environment Guidelines, Heath et al (2022) A new model and terminology for understanding feline emotions, and Heath et al (2018) Understanding feline emotions: ....and their role in problem behaviours.